Overbuild Your Concrete Forms

Every builder who’s poured a concrete slab or walkway has a horror story about forms that bulged or even collapsed under the force of wet concrete. To avoid a horror story of your own, build strong forms. Use 1-1/2-in.-thick boards (2x4s, 2x6s, etc.) except on curves. If you’re using 2x4s or 2x6s, place stakes no more than 3 ft. apart.

If the forms extend below ground, pack soil against them. If they extend more than 6 in. aboveground, reduce the spacing between stakes and brace each one with a second stake and a diagonal “kicker.”

Form Concrete Sidewalk Curves with Hardboard

Fiber cement board siding is intended for exterior walls, but it’s also great stuff for forming curves because it’s flexible and cheap. A 12-in. x 16-ft. plank won’t cost much, and you can cut it to any width you need.

Because it’s so flexible, hardboard needs extra reinforcement to prevent bulging against the force of the concrete. If the forms are belowground, place stakes no more than 3 ft. apart and pack soil against them. For aboveground forms, space stakes 16 in. apart. To form consistent, parallel sides for a curved sidewalk, build one side first. Then use a “gauge board”—a 1×4 with blocks screwed to it—to position the other side.

In wet weather, hardboard can swell and your perfect curves might become wavy. So if rain is forecast, be prepared to cover your hardboard forms.

Keep Stakes Below the Concrete Forms

Stakes that project above forms create a hurdle for your screed board—and screeding concrete is hard enough without obstacles. So before you pour, take five minutes to cut off any protruding stakes. If the tops of your forms are near ground level, make sure your screed board won’t drag against the ground; you may have to skim off a little dirt to clear a path for the board.

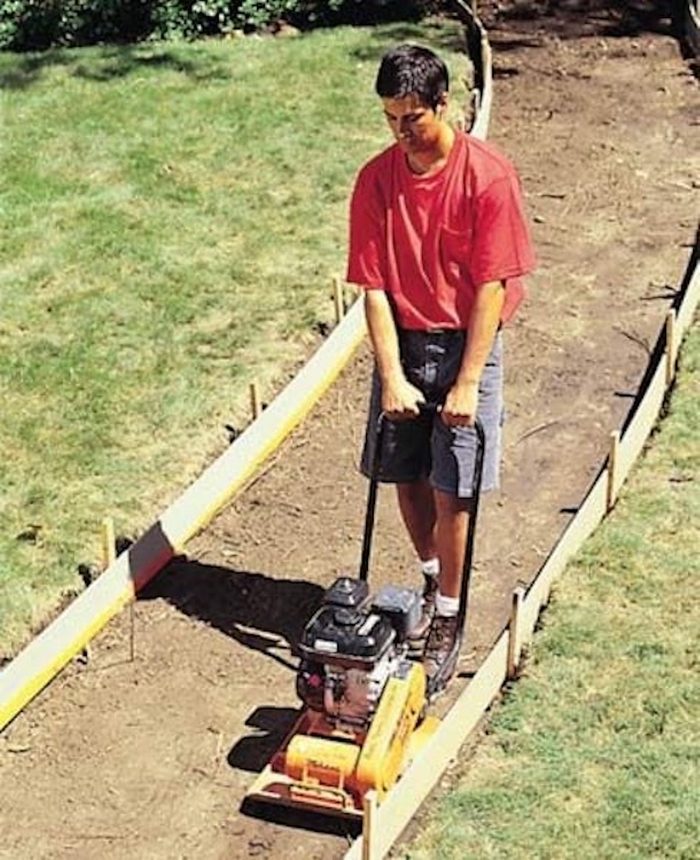

Put Down a Solid Base for Concrete

A firm, well-drained base is the key to crack-free concrete. The best plan for a solid base usually includes compacted soil followed by several inches of a base material such as gravel. But the best base depends on climate and soil conditions. So talk to a local building inspector who’s familiar with conditions in your neighborhood.

Packing the soil with a rented plate compactor is always a good idea, but you may be able to skip the gravel altogether if you have sandy soil.

Plunge Out the Bubbles in the Concrete

When you pour concrete, air pockets get trapped against forms, leaving voids in vertical surfaces. That usually doesn’t matter on sidewalks or driveways. But aboveground, on cement steps, curbs or walls, the results can look like Swiss cheese. To prevent that, just grab a 2×4 and “plunge” all along the forms. Then go all along the forms with a hammer, tapping the sides.

Avoid Too Much Water in the Concrete Mix

When you have concrete delivered, the first words out of the driver’s mouth may be “Should I add some water?” Unless the concrete is too dry to flow down the chute, your answer should be no. The right amount of water is carefully measured at the plant. Extra water weakens the mix. More water makes it easier to work with right away, but will lead to a weaker slab.

If you’re mixing concrete yourself, do this test: Plow a groove in a mound of concrete with a shovel or hoe. The groove should be fairly smooth and hold its shape. If it’s rough and chunky, add a smidgen of water. If it caves in, add more dry concrete.

Don’t Delay Floating the Concrete

After screeding concrete, the next step is to “float” it. Floating forces the stones in the mix down and pulls the cement “cream” to the surface so you can trowel or broom the surface later without snagging chunks of gravel. If you wait too long and the concrete begins to stiffen, drawing the cream up is difficult or impossible. So the time to float is right after screeding.

On a long sidewalk or driveway, it’s best to have a helper who can start floating even before all the screeding is done. There is one reason to delay floating, though: If puddles of water form on the surface after screeding, wait for them to disappear before floating.

On small projects, you can use a hand float made from wood or magnesium. The “mag” float glides easier for less arm strain. But for bigger projects like driveways or patios, don’t mess around with a hand float. Instead, use a bull float. The long handle extends your reach and makes the job easier, while the broad head covers the surface quickly and flattens out any bulges or depressions. To make the surface as flat as possible, float it in both directions.

Cut Deep Control Joints in the Concrete Walkway

The grooves in concrete are called “control joints” because they control cracks in the surface. Concrete shrinks as it dries, so cracks have to happen somewhere. Control joints create straight breaks rather than an ugly spiderweb pattern. They also limit cracks that form later. On a sidewalk, space joints 5 ft. apart or less; on a slab or driveway, no more than 10 ft. apart.

There are two ways to make control joints: Plow them in the wet concrete right after floating or cut them the following day with a saw. You can buy a diamond blade for your circular saw at home centers. Creating joints with a “groover” in wet concrete is less work and less mess. Joints should be at least one-fourth the depth of the concrete.

Finish Concrete with a Broom

Most people reach for a steel trowel when to finish concrete, but the smooth surface it creates is too slippery for outdoors. Instead, drag a broom over the concrete. You’ll get a nonslip texture and hide imperfections left by floating or troweling. You can use a plain old push broom, but a special concrete broom cuts finer lines.

The sooner you start, the rougher the finish. Make your first pass about 15 minutes after floating. If the texture is too rough, smooth it over with a mag float and try again in 15 minutes. Drag the broom over the concrete in parallel, slightly overlapping strokes. You may have to rinse off the broom occasionally to avoid a too-rough finish.

Slow the Concrete Curing Time

Water is essential for the chemical process that makes concrete harden—the longer concrete stays damp, the harder and stronger it gets. One way to slow down drying is to cover concrete with 4-mil plastic sheeting. When concrete is hard enough so you can’t make an impression with your finger, gently spread the plastic. Stretch it out to eliminate wrinkles and weigh down the edges to seal in moisture.

When you see signs of drying, lift the plastic and gently sprinkle on more water. Keep a sidewalk or patio damp for three days. Seven days is best for a driveway. Plastic can cause mottled coloring on concrete, but the splotches disappear in a month or two.

Pros often skip the plastic and spray on a waxy liquid “curing compound” to slow down evaporation. Though not as effective as plastic, curing compounds are easy to apply with a garden sprayer. Curing compounds are available at home centers.