Pouring Concrete Mistakes

Most concrete projects fail because of avoidable errors in mixing or pouring. The harsher the winters where you live, the more important it is to steer clear of the kind of mistakes you’ll learn about here. Poor concrete techniques almost always lead to flaking, deterioration and premature failure. Avoid the top 12 concrete pouring mistakes and you’ll have a project to be proud of for a long time.

Concrete Too Wet

This is probably the easiest concrete mistake to make because properly mixed concrete looks too dry to flow and trowel properly. Don’t be fooled. You should be able to form concrete into a four-inch diameter, four-inch tall pile if it’s mixed properly. Any sloppier than this and the strength of the concrete will diminish.

Concrete Too Dry

Although a less common problem than concrete too wet, too dry is not good either. Portland cement is the active ingredient in concrete, and cement needs sufficient moisture to cure with full strength. If troweling a sample pile of concrete doesn’t create a smooth, wet, muddy surface in three strokes of the trowel, your concrete is probably too dry.

Pouring Too Thin

Concrete can be strong and long lasting, but only if it’s thick enough. Are you pouring a concrete slab for a shed floor or DIY patio? This is the most common application for DIY concrete pouring. Be sure you never make your slab thinner than four inches for any application. Six inches is the minimum thickness for a concrete slab that may see any kind of heavy vehicle traffic.

Expecting Reinforcing Mesh to Stop Cracking

No one wants a concrete project to crack, but don’t put your trust in the kind of standard welded wire mesh typically used for concrete reinforcement. It won’t stop cracking, but it will hold the cracked concrete pieces together.

Mixing your concrete with reinforcing fibers and using reinforcing rods laid down on a 12-in. x 16-in. grid pattern greatly reduces the chance of crack formation. Also, two weeks after pouring, use a masonry saw to make cuts one-third of the way through the thickness of your concrete slab. Make these cuts in a 10-ft. x 10-ft. grid pattern. Any slight cracks that may form will follow the saw cuts and be hidden by them.

Using Old Cement

Portland cement, the active ingredient in concrete, is a perishable commodity. Never use cement or a just-add-water concrete mix that’s more than a year old for any project you care about. Even new cement with hard lumps should not be used for concrete. Hard lumps indicate the cement has gotten moist at some point and lost some of its ability to harden.

Failure to Use Fibers

Too few DIYers know about concrete reinforcing fibers. These thin, short strands of plastic add a lot of strength and crack resistance to any kind of concrete project. Add a pint of fibers to each mixing drum load of concrete and mix as usual. The fibers spread out within the mix and help bind the hardened concrete together. They make a big difference.

Corrosion-Prone Reinforcing Rod

Concrete is strong in compression, but weak when any force tries to pull it apart. This weakness in tension is why concrete is often reinforced with metal rods. The problem is, most concrete reinforcing rods are made of bare steel that’s prone to rust from water that sneaks into the concrete.

When steel rusts, it expands, causing the concrete to flake off and come apart under internal pressure. This is why corrosion-proof reinforcing rod should be used for long-term reliability of concrete projects. Use epoxy-coated, galvanized or fiberglass rebar for all ground-level concrete slabs.

Troweling Too Soon/Too Late

Smoothing concrete with a trowel to give it a nice surface before it hardens is called finishing, and this step has to happen at just the right time.

Ideally, you want to finish concrete when the surface water has dried, but the concrete is still soft and workable. Trowel concrete too early and you’ll get even more surface water forming, leading to a concrete surface that will flake and fail in time. Trowel too late and you won’t be able to create a smooth surface because it’s no longer soft enough. The time to wait before finishing varies depending on air temperature and how wet the concrete is to begin with.

Concrete-to-Skin Contact

The cement in concrete is highly alkaline, and that means it can injure your skin. The tricky thing is, you can get wet concrete on your hands all day long and notice nothing until the end of the day. That’s when red, painful areas of thin, dissolved or cracked skin shows up. Use a trowel and shovel to handle wet concrete. And to be safe, wear gloves.

Weak Concrete Mix

The most economical way to obtain concrete is to mix your own from Portland cement, sand and crushed stone. This is considerably less expensive than buying just-add-water concrete mix in bags.

But beware — if you mix your own, don’t cheat yourself. The standard concrete recipe is one part cement, two parts sand and three parts clean crushed stone. Don’t skimp. Crushed stone is filler, so don’t use any more than the recipe calls for. In fact, use a little less stone proportionally if you have a hard time troweling a nice, smooth surface.

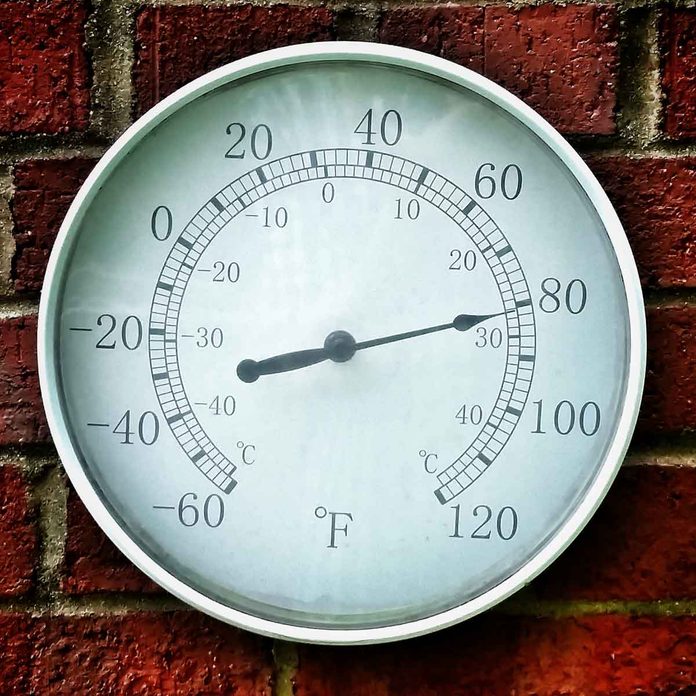

Wrong Air Temperature

This is one DIY to avoid when it’s hot and humid. Pouring concrete when it’s hotter than 80 degrees F is risky because your concrete can begin hardening sooner than you can get it poured and troweled. Pouring concrete when there’s danger of frost is also a problem because concrete loses a tremendous amount of strength if it freezes before curing. Moderate temperatures are always the best for pouring concrete.

Inaccurate or Weak Forming

A poured concrete project is only as accurate as the forms that held the concrete while it was wet. That’s why it pays to check and double-check your forms before any pouring happens.

Strength is another issue. Concrete is really heavy stuff, and the taller your forms the stronger they need to be. “If in doubt, build it stout” definitely applies to concrete forms. A form that blows out during a concrete pour is a disaster, so use lots of wood and braces when building your forms.